The Decade of Vaccine Economics (DOVE), housed at the International Vaccine Access Center at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, aims to generate economic evidence on vaccine impact in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The project began in 2011 and is in its fourth phase. Phases I-III focused on building economic models to estimate the cost of illness, return-on-investment, and the cost of financing vaccine programs. Phase IV aims to expand on previously developed economic models by updating the estimate of the return-on-investment (ROI) of vaccines. Additional DOVE IV projects include collecting primary data on the cost of illness in two LMICs, reviewing existing data on the cost of vaccine-preventable diseases, and piloting contingent valuation methods in Bangladesh.

The Decade of Vaccine Economics (DOVE), housed at the International Vaccine Access Center at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, aims to generate economic evidence on vaccine impact in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The project began in 2011 and is in its fourth phase. Phases I-III focused on building economic models to estimate the cost of illness, return-on-investment, and the cost of financing vaccine programs. Phase IV aims to expand on previously developed economic models by updating the estimate of the return-on-investment (ROI) of vaccines. Additional DOVE IV projects include collecting primary data on the cost of illness in two LMICs, reviewing existing data on the cost of vaccine-preventable diseases, and piloting contingent valuation methods in Bangladesh.

While vaccines are widely regarded as one of the most cost-effective public health interventions, we still lack evidence on the broader economic impact of vaccines, including the costs of illness of vaccine-preventable diseases like pneumonia, diarrhea, and measles.

As part of the DOVE project’s fourth phase, researchers from the International Vaccine Access Center at Johns Hopkins University (IVAC), International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), and Makerere University School of Public Health (MakSPH) have teamed up to empirically estimate the cost of pneumonia, diarrhea, and measles in children under five in Bangladesh and Uganda.

The study collects utilization, cost, and expenditure data for the 201718 fiscal year using a micro-costing approach. Six different surveys were developed to capture these data from the perspective of both patient caretakers and the health care system actors. Facilities from the public and private (for-profit and not-for-profit) sectors, from rural and urban settings, and at every level of care were included. This research will help national and local stakeholders make more informed decisions about the true economic burden of childhood diseases and provide evidence to support ongoing investment in the vaccines targeting these diseases. Read the methods report for more information.

To enable the use of economic estimates beyond the DOVE project, the team designed three learning modules about cost of illness as an economic approach to the burden of disease:

Module 1 – Costs & economic perspective: You will learn about the concept of “cost of illness,” the different costs found in using and providing health care, and the different economic perspectives used to capture all relevant costs.

Module 2 – Collecting data in health care facilities: You will learn how to collect economic data and information, how it can be used, and how we keep it safe and confidential to protect all respondents.

Module 3 – Catastrophic health expenditures: Health care can be expensive. When facing illness, the household may have to take a loan or sell their possessions to afford health care. Sometimes, it is so expensive that people fall into poverty. Catastrophic health expenditures are an indicator that helps measure who is at risk and help program managers improve universal health coverage.

For more information, please contact Gatien de Broucker at gdebroucker@jhu.edu.

Read the policy briefs summarizing the methods and results for Bangladesh and Uganda.

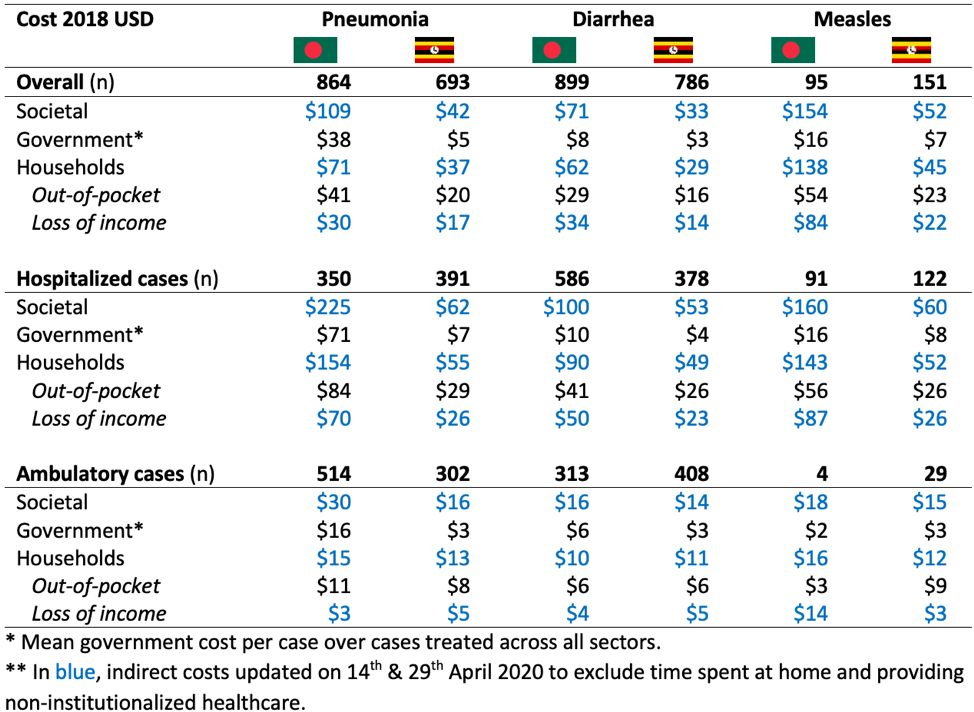

From a societal perspective:

An episode of pneumonia costed US$109 in Bangladesh and $42 in Uganda, on average

An episode of diarrhea costed $71 in Bangladesh and $33 in Uganda, on average

An episode of measles costed $154 in Bangladesh and $52 in Uganda, on average

The economic burden of these disease on society represented 7-12% of the countries’ GDP per capita.

In the following table, the cost estimates for pneumonia, diarrhea, and measles are reported by economic perspective for Bangladesh 🇧🇩 and Uganda 🇺🇬 in 2018 US dollars.

The following documents are available online and on DataVerse:

Data and program files for Bangladesh

Data and program files for and Uganda

We are looking to collaborate with anyone who is collecting or has national or subnational data relevant to economic or vaccine coverage equity in Uganda, Bangladesh, India, Nigeria, or globally or regionally (Sub-Saharan Africa & South-East Asia).

Please contact Bryan Patenaude at bpatena1@jhu.edu.

Cost of illness (COI) data can be generated in two ways: empirically through patient and facility surveys and administrative data or modeled when cost data are available to researchers from secondary sources. COI data from empirical studies provide more comprehensive insights on the use of health care resources at the patient level, compared to costing studies focusing on a specific treatment or program.

First, COI studies usually include costs associated with accessing health care, such as out-of-pocket payments and the opportunity costs of receiving treatment, often invisible to the health care provider. Second, they report the ‘real’ use (compared to the use prescribed in the treatment guidelines) of diagnostic tests, medications, and other supplies as reported in medical records and by the patients themselves. Such estimates are considered ‘real cost’ evidence of the level of economic burden borne by the population and the institutions that serve it.

To better understand and categorize the existing evidence around the COI of childhood diseases, we conducted a systematic literature review to build a cost of illness database of childhood disease in low- and middle-income countries. These data were used to update parameters in the DOVE COI and Return on Investment (ROI) models to reflect the most recent economic and health data available.

The review yielded 37 articles and 267 sets of cost estimates. Here are some key takeaways:

Missing data: There was no cost-of-illness study with cost estimates for hepatitis B, measles, rubella, or yellow fever from primary data (up to 2016). An article on measles and rubella published since then is included in the discussion.

Catastrophic health expenditures: 13 articles compared household expenses to manage illnesses with income and two with other household expenses (food, clothing, rent). An episode of illness represented 1–75% of the household’s monthly income or 10–83% of its monthly expenses.

In most cases, government costs > household costs: Articles that presented both household and government perspectives showed that most often, governments incurred higher costs than households, including non-medical and indirect costs, across countries of all income statuses, with a few notable exceptions.

COI studies follow good costing practices and could provide additional information on the context: For instance, additional information on the occurrence of common situations preventing the application of official clinical guidelines (such as medication stock-outs) would reveal the cost of deficiencies in the health system.

The following documents are available online and on DataVerse:

For more information, please contact Bryan Patenaude at bpatena1@jhu.edu and Gatien de Broucker at gdebroucker@jhu.edu.

Cost of illness (COI) estimates can be measured empirically or generated with models. Models allow us to project the economic benefits of vaccines and estimate vaccine impact in regions lacking empirical data by integrating costs and epidemiological data from different sources.

The DOVE Cost of Illness (DOVE-COI) models estimate the costs averted by vaccination against ten antigens: hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type B, human papillomavirus, Japanese encephalitis, rubella, yellow fever, pneumococcal pneumonia, measles, meningitis, and rotavirus. Focusing on 94 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) from 2001 to 2030, the models estimate three short-term costs averted by vaccines (treatment costs, lost caretaker wages, and transportation costs) and two long-term costs averted (productivity loss due to disability and death). Beyond costs averted, supplemental models use value per statistical life-year methods to estimate the social value of lives saved through preventing disability and death.

Outputs from the DOVE-COI model are frequently used by stakeholders such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to advocate for new vaccine introduction and increased vaccine coverage and to inform investment decisions. The results are also used for the DOVE Return on Investment (DOVE-ROI) analysis.

The figure below showcases the estimated number of deaths averted (right Y-axis) and the economic benefits (left Y-axis) linked to immunization against ten pathogens in 94 low- and middle-income countries from 2011 to 2030, using three different valuation approaches: cost of illness (COI), value of statistical life (VSL), and value of statistical life-year (VSLY).

For more information, please contact Bryan Patenaude at bpatenaude@jhu.edu.

|

Study highlights The results demonstrate a continued high return on investment from immunization programs over the two decades:

|

Vaccines are not only life-saving, they are also a smart economic investment. For a few dollars per child, vaccines can prevent disease and disabilities that last a lifetime, saving millions of dollars in potential health care spending by households and the health system. Vaccines can save lost wages and reduce productivity loss due to illness and death, contributing further to economic growth. Return on Investment (ROI) estimates provide important evidence that supports vaccine introduction decisions. In an earlier study (Ozawa et al., 2016), we estimated that projected immunizations will yield a net return about 16 times greater than costs over the decade. Immunization has a higher return on investment than many other interventions like preschool education, public infrastructure, community health workers, government bonds, and cardiovascular disease research.

Building on the lessons learned from the previous phases, the DOVE ROI analysis measured the ratio of the total economic benefits to the total immunization program costs for ten antigens in 94 low- and middle-income countries during the “Decade of Vaccines” 2011–2020 and the following decade (2021–2030). The analysis aligned outputs from the DOVE Cost of Illness (COI) models and the Costing, Financing and Funding Gap (CFF) model, updated with additional data inputs and several model structural changes. The analysis leveraged new data generated from the primary data collection and systematic review of cost of illness also conducted under the fourth iteration of the DOVE project.

Sim, So Yoon, Elizabeth Watts, Dagna Constenla, Logan Brenzel, & Bryan Patenaude. (2020). Return On Investment From Immunization Against 10 Pathogens In 94 Low- And Middle-Income Countries, 2011–30. Health Affairs, 39(8). DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00103

The analysis was a collaborative exercise between the Johns Hopkins International Vaccine Access Center (IVAC) and experts in immunization economics and financing, who together comprise the DOVE-ROI Core Group. Previously referred to as “the Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) Costing & Financing Steering Committee,” the DOVE-ROI Core Group is an advisory body for the ROI analysis that offered technical guidance for the updated methodology, provided support in collecting model inputs, and provided peer-review. Its members are listed under “People” below.

Full publications of the results and methods of the DOVE ROI model:

For more information, please contact Bryan Patenaude at bpatenaude@jhu.edu.

Contingent valuation (CV) is a type of stated-preference study that uses surveys to elicit willingness-to-pay (WTP) for goods and services that have not yet been introduced into the market, subject to a budget constraint. The four common CV methods used are dichotomous choice, open-ended questions, bidding game, and payment card.

The DOVE-CV project focuses on how best to conduct CV studies to obtain more valid and less biased WTP estimates for mortality risk reductions in resource-poor settings. To this end, we have performed a literature review on contingent valuation studies from low- and middle-income countries in order to make a preliminary assessment of the conditions and resources needed to apply these methods and explore the current evidence gaps.

With emphasis on Gavi-Asia countries (Bangladesh, specifically) the DOVE-CV team is performing a pilot study to understand what methods are best suited for the Bangladesh context, as well as investigating the role of cognitive interviews in ensuring participants’ understanding of questions to allow for more valid WTP estimates. We will be eliciting WTP for mortality risk reductions for vaccine-preventable diseases through a quasi-randomized convenience sample of every tenth patient at two health facilities in Bangladesh. This project is currently in the planning phase.

For more information, please contact Deborah Odihi at dodihi1@jhu.edu.

Dr. Bryan Patenaude, Principal Investigator 2019–present

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

bpatena1@jhu.edu

Dr. Dagna Constenla, Principal Investigator 2016–2018

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

dconste1@jhu.edu

Gatien de Broucker, Health economist, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Dr. Elizabeth Ekirapa-Kiracho,* Co-investigator – Uganda, Makerere University School of Public Health

Dr. Md. Jasim Uddin,* Co-investigator – Bangladesh, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh

*co-Principal Investigator

Gatien de Broucker, Health economist, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Margaret (Peggy) Gross, Informationist, Johns Hopkins Welch Medical Library

So Yoon (Yoonie) Sim, Health economist, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Sarah Alkenbrack, Senior Health Economist, The World Bank Group

Logan Brenzel, Senior Program Officer, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Tania Cernuschi, Technical Officer, Vaccine Pricing, Supply, Procurement, World Health Organization

Anais Colombini, Senior Program Manager, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

Santiago Cornejo, Senior Specialist, Immunization Financing, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

Emily Dansereau, Program Officer, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Joe Dieleman, Assistant Professor, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), University of Washington

John Fitzsimmons, Pan-American Health Organization

Ulla Griffiths, Senior Advisor, Immunization Financing and Health Systems Strengthening, UNICEF

Dan Hogan, Head, Corporate Performance Monitoring & Measurement, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

Xiao Xian Huang, Health Economist, World Health Organization

Raymond Hutubessy, Health Economist, World Health Organization

Hope Johnson, Director, Monitoring & Evaluation, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

Jeremy Lauer, Economist, World Health Organization

Tewodaj Mengistu, Senior Program Officer, Corporate Performance Monitoring & Measurement, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

Thomas O’Connell, Health System Advisor, Health Governance and Financing, World Health Organization

Claudio Politi, Health Economist, World Health Organization

Lisa Robinson, Senior Research Scientist, Center for Health Decision Science, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

Stephane Verguet, Assistant Professor of Global Health, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

Dagna Constenla, Project lead, Director of Economics and Finance (Sept. 2016–Jan. 2019)

So Yoon (Yoonie) Sim, Project Coordinator, Health Economist/Research Associate

Elizabeth (Libby) Watts, Project Coordinator, Health Economist/Research Associate

Deborah Odihi, Health economist, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Gatien de Broucker, Health economist, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Sayem Ahmed, Health economist, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh

Dr. Md. Jasim Uddin,* Co-investigator – Bangladesh, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh

Lisa Robinson, Health economist, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

For many years, the Immunization Economics Community of Practice has supported researchers, policymakers, and practitioners around the world to use economic evidence to make better immunization decisions so that limited resources can save more lives.

Our work has been generously supported by the Gates Foundation and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, but our current funding ends this year. We are now seeking donations to help us bridge this transition and keep the community alive.

Donate